Writing with Ghosts: A chat with bell hooks and James Hillman across time, race, and imagination

Eavesdrop on a conversation between two luminaries - Black feminist thinker bell hooks and archetypal psychologist James Hillman - about how the stories of the past still shape our world.

Earlier this month, I shared a bit of a personal rant about my frustration with the myopic Euro-American dominance of my graduate school curriculum, which I won’t rehash in detail here; please check out the piece “Fly in the Buttermilk” in its written and recited forms for more on that.

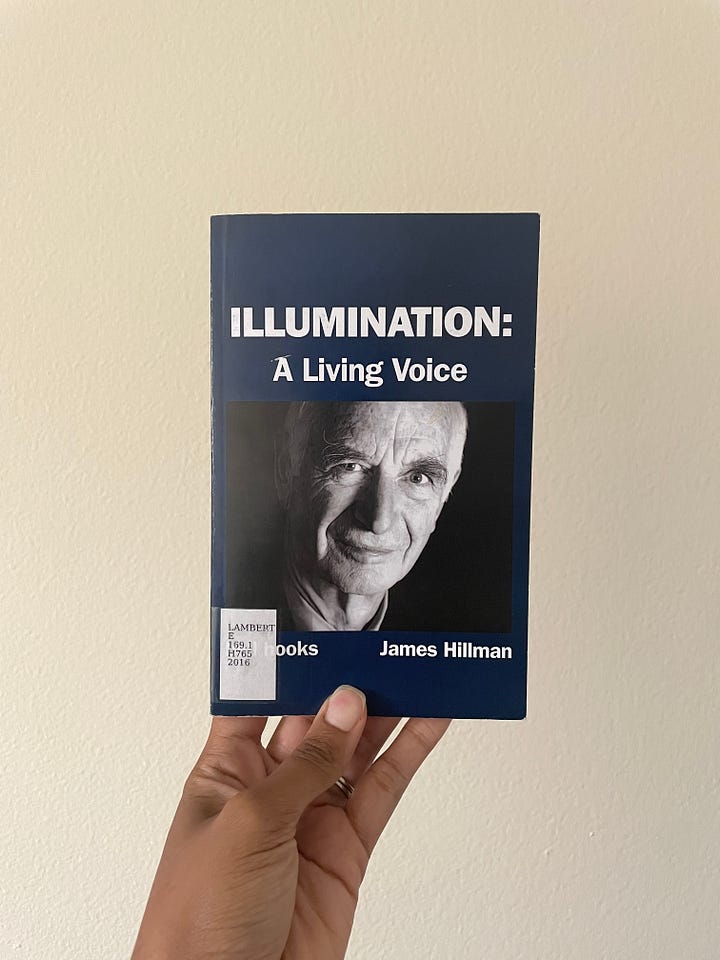

I can’t quite remember where I heard the phrase “writing with ghosts” but I’ve been ruminating on it for months. The following excerpts are from a conversation between Black feminist scholar bell hooks and archetypal psychologist James Hillman in Illumination: A Living Voice. Their chat illustrates the blending of the sociopolitical and the imaginal that preceded my rant and I hunger for in my graduate program. They converse with the specter of racial capitalism and war in the U.S, but they are also in conversation with their intellectual ghosts and the ancestors they will eventually become.

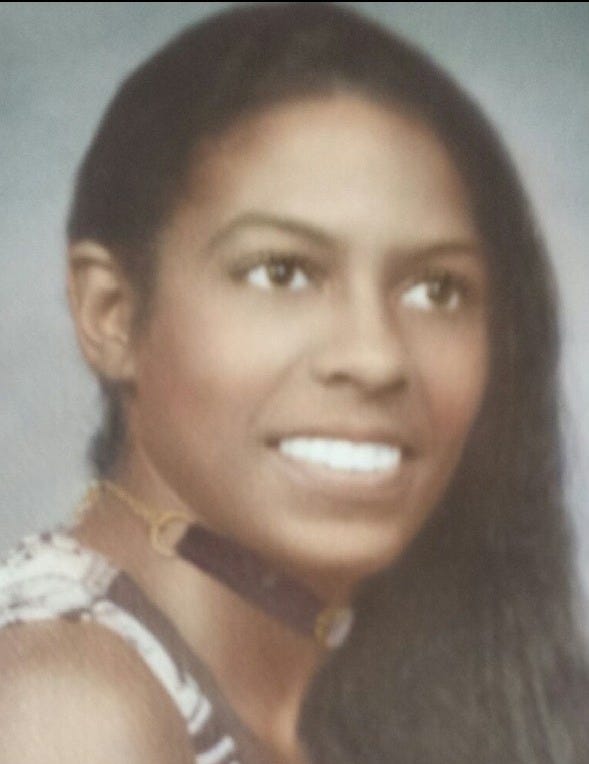

Some would say that hooks and Hillman were unlikely friends. Illumination: A Living Voice was published in 2006 when bell hooks was about 54 years old and James Hillman about 80. This was an intergenerational, interracial friendship of people with foundationally different upbringings. But bell hooks was deeply spiritual (more affectionately, woo), blending feminist scholarship with Buddhist and Christian traditions. It makes perfect sense to me that she would befriend Hillman, who made a career of studying suffering and the “care of souls,” and they understood the transgressive nature of their relationship. Per hooks,

James and I were particularly aware that certain conversations across race, class, gender, rarely take place in our society. We consider it a radical intervention on systems of domination that we made a pact to talk together–meeting through the years–for intense conversation. My book Moving Beyond Race is dedicated to James Hillman, “beloved comrade” (Introduction, v).

Notes on Method: Illumination, now out of print, is a published, informal conversation between two friends near the end of one of their lives. It is both reflective and visionary, possessing the character of two elders sitting on a porch in rocking chairs watching children play. I’ve interspersed my comments on their conversation in the transcription, clearly denoted by my last name, as if I am there on the porch with them, minding grown folks business and butting in where I shouldn’t. The book’s text is the transcription of a conversation between the two of them, so there are spelling and grammatical errors and colloquialisms that don’t quite render the same in text. Such is the nature of oral history...

On imagination, anti-intellectualism, and civil religion in the U.S. (pp. 14-16)

hooks: When we talk about what it means to live and work in an anti-intellectual society, we really have to begin with first acknowledging that the United States was not always an anti-intellectual society. But then again, the very creation of the United States was in many ways an act of imagination.

Hillman: Oh, huge imagination. And those founding fathers who were worshipped [sic] as secular saints with temples in Washington, great white temples for each one of them, with a huge overdimensional [sic] size to them–Lincoln is huge in the Lincoln Memorial. If you go to Egypt, you find statues such as the pharoahs or the gods. So we have these secular gods, and we all talk about the founders; and Scalia and the strict constructionists are members of that cult of the founding fathers. They’re all fathers. There’s not a founding mother in the bunch.

hooks: How as you pointed out in an earlier discussion, what people erase is the sort of thinking, intellectual mind of the so-called founding fathers.

Hillman: I’m glad you brought me back to that because I was really going against the cult of that. They themselves. They were extraordinary. Interesting [sic] enough they nearly all had the same kind of library. They had a small library. They all read their books many times. They had the classic stuff of the Roman thinkers about statesmen like Cicero, the lives of Plutarch. They knew the Classical foundation. Madison, Jefferson, the signers of the Declaration, the founders of the Constitution. Where did they come up with it? They really came up with ideas based on historical writing. They had intellectual knowledge. Even Andrew Jackson, the man of the people, the tough soldier who started that death march from Florida–a horrible, cruel man in one way. You read him and his letters were astonishing. We had an intellectual tradition. The leaders of the country knew something. It was tied in with their political aspiration–Calhoun, from South Carolina, a nasty man in many ways, was tied intellectually with his political abilities. We don’t have that at all.

Gilbert: I understand violence as innate to civil religion in the U.S.. It must follow that violence underlies western epistemologies, per colonial and decolonial thinkers. Either that, or the so-called founding fathers experienced some deep cognitive dissonance. Do we throw out the entire world building framework? “Take what we need and leave the rest?” Learn the rules to break them? I grapple with these questions as I grow ever more frustrated with the exhausting whiteness of my grad school curriculum. Here I’m also thinking about my budding interest in African Diaspora Religions and how indigenous African religious customs had to acculturate to whiteness to survive the slave trade. Hillman’s comments on the founding fathers epitomize the sort of intellectual reverence I deal with in class regarding the “great legacy of Europe.” I am the fourth generation of my family in Oklahoma. I cannot compartmentalize Andrew Jackson’s atrocities against indigenous folks to marvel at the magnificence of his intellect.

On dementia, emotional intelligence, and the imagination’s capacity to bridge the liminal space between life and the hereafter (pp. 24-26)

hooks: Exactly. And we might want to know how something of the world [my mother] has entered. That’s why I say, Remember Me As Loving You, what amazes me is emotional intelligence that can remain and become more clarified in the absence of that connecting memory that we are so addicted to: Does A connect to B. When people go to visit mom and they say, do you know who I am? In this sort of interrogation, you can see the agitation that begins to build in the person.

Hillman: They are very threatened. I know this very well from my mother, my sister, my brother’s wife. They are very afraid of leaving what they call and what the culture calls “reality.” On the other side of reality is insanity, or on the other side of reality is death, or something. And they cannot accept [sic]. They are always trying to bring back the person. They’re always trying to bring the person who is halfway elsewhere back.

hooks: We never perceive our emotional universe to be the same on par with that universe of ideas and thinking and rationality.

Hillman: But in many people it is impoverished, they have no idea of that emotional universe.

hooks: The interesting thing is that so many who are impoverished, once they begin to have dementia, and once they begin to no longer have the capacity to rely on a western–

Hillman: Reality.

hooks: They begin to nurture that emotional universe. They are almost like animals, they’re sense of smell, touch, hearing–all of it becomes heightened.

Hillman: And the perception of the other. So often because the other is coming in on the wrong level; they close off even more.

hooks: Exactly, so here we have this whole culture of people who could in fact be teaching us more about that power of emotional intelligence, and we incarcerate them. It’s like we put them in prison; prisons for the elderly. And we’re going back to the imagination.

Hillman: This is a huge thing that you’re talking about. What is this doing to the culture?

hooks: We numb them. For I can tell you, what happens in these nursing homes is mind destroying. There is no conversation. Television is going 24/7. Even magic comes through the television. There is not a moment where there is silence. There is not a moment of choice where you might turn on your radio. TV’s all controlled and it’s detrimental to the imagination. As you say, it invites a shutting down.

Gilbert: Earlier this year my last grandparent died from frontotemporal dementia. She had been quite lively and chatty before her health declined, and my mom (who began full-time care for her in Fall 2023), would describe and share videos with me of Mema’s visible frustration with losing her fierce independence and her ability to speak coherently. The details my mother shared with me about my grandmother’s physical state at that time of her death paint a grim, gruesome picture, so I am happy neither Mema nor Mom are suffering in that way anymore. I am also grateful for the Tibetan Buddhist teachings about the Bardo that I learned during my Buddhist traditions course over the winter because that language gave me a relevant concept to contemplate on the transformative possibilities of liminality rather than fixate on my grandmother’s physical decline.

On golf courses and ancestral desecration (p. 27-28)

hooks: Wait, you would do what you did with me in Kentucky on the golf course; the Civil War state. We would try to evoke the memories of the dead underneath that golf course; and to remember to piece together the fragments that golf course is trying to destroy.

Hillman: That’s right. The history these greens had wiped out.

hooks: And remember the big, huge holes? It is a moment to reflect that clearly there is no respect for the ancestors. When you think about how many countries that would think that it’s completely, psychically detrimental to build your homes on the bodies of the ancestral dead. And here, it’s like it’s engaging, it’s cute–”Let’s build our home on the slavery myth [sic]. How many gated communities in the South are called the Beautiful, [sic] the whole idea, that you can take this genuine history of bodies, of slaughter and of survival and turn it into this seamless harmony of eternal consumption in praise of the material.

Gilbert: Here, Hillman is wrestling with his desire for a peaceful retirement and knowing that he has more work to do. I’m not sure what golf course in Kentucky they are referring to, but I know what it means to bear witness as systems of dominance desecrate the land and build their playgrounds on the bones of your loved ones. #FreePalestine #WaterIsLife #BlackWallStreet #SenecaVillage

bell hooks’ thoughts on the title “public intellectual” (p. 36)

hooks: That’s why I’ve always eschewed that term public intellectual, because I felt particularly that it masked for my students the reality of the kind of work I did. That the kind of work I did like reading a book a day, going back and forth was really hard, lonely work. It was not about giving commentary on CNN.

Gilbert: This summer as I was writing comp exams for my master’s degree, I was stricken by how isolating and difficult a writer’s work really is. It made me question whether I wanted to continue pursuing my Ph.D. (I do), and eventually publish a book (I do). I was seriously considering letting grad school and this public research practice go, though. I’m learning how to stay sane while spending hours every day alone and staring at a computer and books, just begging my brain to come up with something.

On melancholy (pp. 51-52)

Hillman: Also, what keeps you going when there is nothing around? Or at least, what allows you to sit in the melancholy. You don’t have to go anywhere or do anything. But if you can realize there’s something here where I am melancholy.

hooks: You said that, James, I immediately thought of the poetics of the blues, and that in many ways, both the so-called negro spirituals and the blues were both forms of meditation. They were about just that. I'm sitting here. I'm sitting.

Hillman: That's it. I'm sitting here. Nowhere to go.

hooks: “I've had my fun, if I don't get well no more.” Think about that blues lyric: “I've had my fun, if I don't get well no more.” What is that evoking? it's evoking a sense of what role pleasure might play in life, it's evoking a sense of –is this Paul in Corinthians saying, “I've learned to be content with my lot?” I think that's very different from the collective despair of so many African Americans today. I've had so many black folk talk to me about death and a feeling that their lives have no meaning. Because without Soul life has no meaning.

Gilbert: I am a person who delights in melancholy, and this snippet on the blues as melancholic meditation is my kind of carrying on. I don’t know enough about the genre to write intelligently about it right now, but I intend to change that one day. Fun Fact: I wish I could live to be about 200-250 years old (not forever because that sounds like hell) so I could learn a couple instruments and become a Blues singer.

On isolation and writing that simultaneously transcends time, weaves time, and nourishes one’s soul (pp. 77-85)

hooks: I would say the most passionate interest I've had for a long time was around gender and feminism, and I don't think I'll ever move away from that completely. For even in the contemplation of what does solitude mean for a woman who is moving toward sixty, who is alone, I always have this realization about gender difference, that interesting men, when they seek to move out of solitude, there is always something or somebody waiting. I don't see the same thing for women. When a woman goes into a deeper, a more cloistered or contemplative life, she sort of becomes stuck there. She becomes invisible. No one is waiting for her to leave the space of contemplation to return to a world of visibility and speaking. I still think there's tremendous work to be done on the question of women in solitude, and aging women in solitude.

Hillman: You know they use Jungian language for that. They talk about this third stage of life as the crone, where she becomes a wise woman. And in the Greek mythology, the figure of Hera had three phases. One was Hebe, which we have Hebephelia [sic] now, and there were different levels of the hillside where the temples were. And the third one was the left one, the Greek term for this was, “one who has been left.” So a woman's life is not just through course of time, as I see it, that you're young, then you're married, and then you're left, but all through women's nature is a piece of the left one, who is an isolation, who is in mourning, who has that depth of solitude in her, and I think it's there all that time.

hooks: A thinking woman is by definition isolated.

[fast forward]

Hillman: I think there's another way to give your work long-lasting value, longevity. And that is by incorporating in the work those great thoughts, ideas, depth that comes from a tradition. When your work is embodying these long-term values, whether it's Platonism, or Aristotelianism, or Catholicism, certain deep, strong ideas, myths, and so on, that gives the work longevity. Because those are the things that have lived for two thousand years, and even three thousand and four thousand years. Even biblical stuff. Isn't that what Toni Morrison does? Bring in some way the biblical?

hooks: I did my dissertation on Toni Morrison, but I'm not very interested in her recent books.

Hillman: I mentioned that as one example. By bringing in certain things that have been alive for a long time. You give your work longevity. it speaks to any generation, even if it's forgotten through modern teenage, high school, college culture. It still goes on speaking. And that's the transition I think that you're making now. You are moving away from criticism, analysis of what's going on today to what really matters. That's my question. What is really important still to do?

hooks: What we keep saying, you and I, is that one thing that is still important to do is to write and speak about the soul.

Hillman: Yes, that's a long-time value. And no [sic] spoken about.

hooks: I think one of the tensions I see in myself, having come through feminist theory, is let's face it, feminism in general has not been particularly open to any kind of soul work. In fact, it's been hostile in many ways to an interior language because it's been focused on outer manifestations of power. So part of what's driving me and will drive me in the next 20 years, if I'm alive, is this whole question of should, of meaning, of how we give life meaning.

Hillman: And how we can show that in the work itself. The work itself embodies some of that soul quality. It isn't so much to talk about it, but it comes out in the work. When I think of Margot's painting [wife Margot McLean-Hillman], something comes out through her painting that just comes out through her hand. And it should come out in the work, when you're writing and thinking. So the deepening of the isolation, being an older woman not neglected, or cast out, is one of the ways the soul will come into the work. I think it's that way. It doesn't come into the work through being successful.

hooks: That's why I feel that for me, it's the ecstasy of ideas. That something of what I feel I want to convey.

Hillman: That's the alchemical mind.

hooks: I especially want to convey this to young females that this intellectual life that I've chosen, has been a life of tremendous ecstasy for me.

Hillman: Great.

hooks: I have found it to be even extraordinarily erotic. Sometimes I would feel so driven with ideas that I would be sitting, in the old days of the typewriter or at my desk, feeling this sort of surge that I would also feel erotic, this surge.

Hillman: It feeds the body.

hooks: It is I think about life, that sense of how ideas take as beyond [sic] ourselves. When I get those letters from people that say I've read this book of yours and it changed my life–

Gilbert: This builds nicely on the previous section about working in isolation for public consumption. First, I think a lot about how being married prevents me from being even more hermit-like and isolated than I probably would be otherwise. It’s an interesting dance to navigate my desire for solitude and companionship, as well as writing alone to share in an online community. Second, I write because I cannot stop, because it nourishes me, because something in the way that I am needs to do it. And it is my deepest desire to write in a way that feeds the souls of others, too, and sustains my livelihood. Also, I believe that my best years will be my crone years, so I tend to make major decisions with the end of life in mind.

On speaking with the dead (pp. 87-88)

Hillman: But are you in any way already connected to the dead?

hooks: I feel like I'm too connected to the dead.

Hillman: This goes back to what we've been talking about. The border between the dead and the living is not that sharp. The writer of The Prince, Machiavelli, when he came home in the evening, and he changed his clothes, he sat at a long table and entertained a whole host of people who were not living there. They were dead. They were his figures, figures who had either written books, or heroes of the past, and he had these imaginary conversations with the dead. The dead is the wrong phrase. These are the living images you are living among and supported by… He lived for them, with them, he thought in terms of them. And I think we need to have that. When you have students, they have to begin to find out who their ancestors are– not just their parents, or even their grandparents, who are very important I think but their mental, their spiritual, their intellectual, their musical ancestors– and be true to them

Gilbert: I want to close our conversation here by referring back to my rant. Who are you thinking with? What ghosts inform your work? Let me know in the comments.

Wow thank you for sharing this conversation and adding in your perspective! I love your question –what ghosts are we thinking with. I feel like I'm constantly inspired and thinking with ghosts whose names I'm still learning, whose stories are still revealing themselves. I live for the journey of discovering their names and stories as I discover myself.