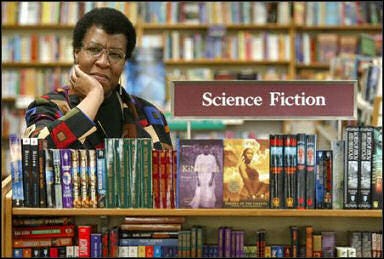

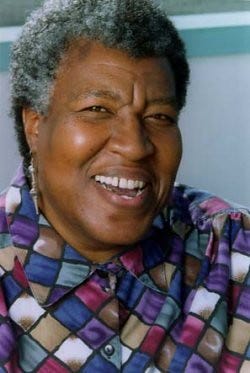

You Don’t Need Another Octavia Butler Think Piece

Octavia E. Butler's Parables series plucks ancient threads in contemporary U.S. sociopolitical issues, including religious nationalism, right-wing extremism, and systemic violence.

You don’t need another Octavia E. Butler think piece. Not from me, anyway. I will spare you from my exuberant stanning this week because there are dozens of Butler enthusiasts who’ve released pieces about her unfinished series of post-apocalyptic novels known as The Parables: Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents. She published the stories in the 1990s, and they depict a United States suffering the aftermath of ecological collapse, wealth inequality, privatization, and white Christian nationalism. The date that kicked off the series was July 20, 2024, so you may have seen a higher volume of content about Octavia and the series protagonist Lauren Olamina over the weekend. There are brilliant people who have shared detailed summaries and exposition on the prophetic nature of The Parables. To get you started, I suggest following the Octavia E. Butler Legacy Network on Instagram, reading “‘Parable of the Sower’ is Now, Says Gen Z” by Aina Marzia, and watching “How Republicans Will Turn Trump into a God” by Kimberly Nicole Foster if you want to bless yourself.

People describe Butler as a prophet for writing those novels; whether she was divinely inspired1 is less important for this conversation. Instead, by focusing on the definition of prophet that emphasizes visionary leadership - the ability to recognize patterns and project them forward - we can see prophecy as the outcome of a series of events. In that light, a prophecy is subject to influence rather than an immovable matter of fate. Put another way, if The Parables predict our future then Butler has offered readers a skeleton key for unraveling the current sociopolitical climate and transforming our communities.

The Parables are so good because they are tangible, because we see and feel ourselves in them. They became posthumous New York Times bestsellers because the stories are ominously and poignantly similar to contemporary U.S. politics. But can we talk about it, though? What exactly is striking such a scary chord within us? Instead of (further) opining about the novels, I’m offering modified excerpts from papers I wrote about myth, extremism, and violence in the U.S. I hope Octavia E. Butler’s influence here is clear, and that this narrative does justice to her visionary legacy.

Myth in the history and present of religious nationalism: Myth has an ongoing impact on sociopolitical discourse, and my research calls attention to applications of mythology that abuse the teachings and symbols therein. For example, it is common knowledge that the Nazi Party misappropriated the swastika, once representing peace and good fortune, as a symbol of their hateful ideology during the Holocaust. The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) has built an online database that maps anti-government extremist organizations in the United States called HateWatch. One such example is the Neo-Völkisch sect that uses “imagery and myths of a romanticized Viking era to transcend nationalism and wield whiteness to suit their ill-conceived ends” (SPLC)2. The term folkish is a near-direct reference to the ethnocentric German volkisch nationalism that motivated Nazi esoteric and mystical research in the SS-Ahnenerbe, the branch of the SS that researched “the ancient roots of German–and by extension ‘Aryan’ –culture, and therefore much of the work done by its members made use of philology, folklore, and archaeology as windows into the pre-Christian past” (Moynihan and Flowers 26)3. Far-right conservative ideology such as that of the Nazi party still motivates contemporary violence. Recent examples of this violence include the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church shooting in Charleston, South Carolina in 2015, the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017, the Tree of Life Synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 2018, and perhaps most notoriously, the assault on the U.S. Capitol in 2021. Far-right conservatism was either directly or ideologically linked to each of these high-profile cases that made national headlines.

Connections among Greco-Roman epic heroes, the military, and right-wing extremism: The Iliad has long been a rich and useful text for helping modern heroic figures like soldiers to frame and critique their experiences in the armed services. Johnathan Shay has demonstrated the parallel traumas between modern combat veterans and Greek heroes in his popular books Achilles in Vietnam and Odysseus in America. Bryan Doerries and Theater of War Productions have also continued Shay’s legacy and that of the ancient poets like Homer and Aeschylus who used their art to critically analyze social issues. The work of investigative reporter Ben Makuch formerly at VICE News has further advanced the work by shedding light on the pipeline between U.S. military veterans and far-right extremist ideology through the docuseries American Terror. In the aftermath of the January 6, 2021 assault on the U.S Capitol, Makuch revealed that there is a minor correlation between combat experience and participation in religious and/or racial extremism domestically: as of December 2022, 545 veterans of the U.S. armed services had been charged with or convicted of extremist acts since 1990, with 163 of those vets connected to the January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol, according to data from The National Consortium for Terrorism and the Study of Terrorism. Vets and first responders possess highly sought skills and are heavily recruited amongst right-wing extremist groups for their combat, engineering, and medical experience. In fact, the Anti-Defamation League released a report in September 2022 which revealed that the Oath Keepers, an anti-government extremist militia, had nearly 400 military or law enforcement personnel in their ranks. The Oath Keepers were one of the groups most prominently active in the January 6 coup attempt, which could help explain why the attackers were able to penetrate the building so effectively.

Systemic negligence and radicalization: A barometer for the ways that cancerous hate groups have been permitted to proliferate in the U.S. was cited in a joint report from the Federal Bureau of Investigation and Department of Homeland Security released in 20214. This report stated that the “greatest terrorism threat to the Homeland we face today is posed by lone offenders, often radicalized online, who look to attack soft targets with easily accessible weapons” (2). These beliefs fester due to the systemic negligence of the U.S, an area of inquiry that warrants additional research. Early indicators to support this assertion include the increasing levels of loneliness and isolation among members of individualistic cultures5, especially returned veterans, and the historical precedent for the intermingling of White supremacist ideology with military training. In the docuseries, Iraq War veteran Kristofer Goldsmith cited his disillusionment with the United States’ occupation of Iraq and the negligence of the military for leading him into the fold of right-wing hate groups after his discharge from the Army without G.I. benefits for attempting to end his own life (see video). In the face of unspeakable violence and the stress of war, Goldsmith was left without the tools to metabolize his grief and loneliness. He could no longer use his capacity to deal death only in the ways of which the social order approves, so he turned that rage and existential loathing on himself, then on the system from which he inherited that trauma shunned and isolated him.

Sedition and the far-right: Kathleen Belew, Associate Professor of History at Northwestern University, stresses how hate groups that embrace ethno-nationalist ideology like those that welcomed Goldsmith and motivated World War II continue to proliferate due to systemic negligence, as indicated by the failed sedition trial that occurred in Fort Smith, Arkansas in 1988. During this trial, U.S. prosecutors tried unsuccessfully to convict members of a network of white supremacist organizations for conspiring to overthrow the United States government. According to Belew, that all 13 of the defendants received acquittals in the trial has only emboldened the action of the ultra-conservative right since then, the ramifications of which we have continued to see through acts of domestic terror that are influenced by or in response to U.S. militarism (Makuch et al). Further, there is a tendency for the U.S. to experience upticks in far-right activity after military interventions. Historical examples of this increase include Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate soldier who then became the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan after the Civil War; George Lincoln Rockwell, a U.S. Navy vet who established the American Nazi Party post-World War II; and Timothy McVeigh who was in the Army before bombing the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

Violence in U.S. civil religion: Atheists and cynics might argue that leaders of theocratic societies such as Ancient Greece contrive or project divine mandates to rationalize their imperialistic inclinations. There are certainly numerous examples of modern nations invoking the divine or some other type of benevolence to justify their political maneuvers. This is a common critique that has been levied at the United States while it occupied Iraq for eight years under the guise of rooting out nuclear weapons and extremist fundamentalists after the events of 9/11. One may even make this critique of the recent Russian invasion of Ukraine, a conflict that Vladimir Putin has previously rationalized by overstating the involvement of ideologically ultra-conservative fighters in the Ukrainian military. Further, the United States rationalized the violence of westward expansion by invoking providence through the concept of manifest destiny. Through reflecting on the works of Williams and Alexander (1994) and Fairbanks (1981), Roberta Coles defines civil religion as “a set of myths that seeks consensus, attempts to provide a sacred canopy to a diverse community, and gives meaning to the community's existence” (403)6. For Coles, manifest destiny is central to U.S. civil religion because it edifies the long-held cultural belief in American superiority that informs this country’s geo-political behavior (404). I seek to extend Coles’ claim by arguing that, like the Homeric hero, a core element of the United States’ civil religion is violence as demonstrated through such historic examples as our use of manifest destiny and genocidal violence against indigenous communities to expand the country’s borders. Additional examples include systematizing and expanding the practice of chattel slavery, our Constitutional protection of firearms and the cultural acceptance of the mass shootings that adhering to that social contract engenders, and the disproportionality of the country’s defense budget when compared with that for education.

TLDR; The terroristic acts of violence that hate groups enact are directly linked to civil religion in the U.S. I see them as sociopolitical descendants of the genocide of indigenous people during colonial history and westward expansion, and the proliferation of mass shootings that have come from our civic exaltation of guns and the Second Amendment of the United States Constitution. These conclusions underscore that violence is the very bedrock of the United States7 and the framing of the city on a hill self-image that our country’s leaders have erected. The structure as it stands is unsustainable and it will crumble if it is not reinforced through increasing levels of violence via cracking down on civil unrest and domestic terrorism á la martial law or, more optimistically, through a complete overhaul of the social contract and a new set of institutions that vie for life and collective prosperity instead of death and incessant violence.

Note: This post contains affiliate links. If you choose to purchase the books using the Bookshop affiliate link, I will receive a small commission on your purchase.

See Streeby, Shelley. “Radical Reproduction: Octavia E. Butler’s Histofuturist Archiving as Speculative Theory.” https://doi.org/10.1080/00497878.2018.1518619.

See “Neo-Völkisch.” Southern Poverty Law Center, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/ideology/neo-volkisch.

See Moynihan, Michael, and Stephen E. Flowers. The Secret King: The Myth and Reality of Nazi Occultism, Feral House, 2007.

See “Strategic Intelligence Assessment and Data on Domestic Terrorism.” Federal Bureau of Investigation, May 2021, https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/fbi-dhs-domestic-terrorism-strategic-report.pdf/view.

See Summers, Juana. “America Has a Loneliness Epidemic. Here Are 6 Steps to Address It.” NPR, 2 May 2023. https://www.npr.org/2023/05/02/1173418268/loneliness-connection-mental-health-dementia-surgeon-general.

See Coles, Roberta L. “Manifest Destiny Adapted for 1990s’ War Discourse: Mission and Destiny Intertwined.” Sociology of Religion, vol. 63, no. 4, 2002, p. 403. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.2307/3712300.

https://www.google.com/url?q=